Climate emergency declarations are like a rash. There was a pre-COVID sense of urgency developing, energised by the movement led by Greta Thunberg. According to a 2019 survey, 79% of EU citizens saw climate change as a very serious problem (up from 74% in 2017). The transport sector is the tough nut to crack if we are to hope to tackle this and achieve a net zero CO2 emissions economy in 30 years’ time. Intentions to address climate change are mounting. Attitudes are changing.

But what of changing behaviours in transport? According to the International Energy Agency, SUVs made up 36% of total car sales in Europe for 2019, continuing an upward trend and pushing transport emissions in the wrong direction. Unless cognitive dissonance is rife, perhaps it’s the 26% in the survey above (who are less concerned about climate change) who are the buyers? In any case, people are exercising choice where they have it, and motor manufacturers are only too pleased to influence such choice in the interests of profit margins.

I believe that people’s behaviour is largely a product of the system within which they exist. Individuals can and do change their transport behaviours, but many more may be minded to, and encouraged and enabled to change if their circumstances were changed. COVID-19 and the accompanying lockdown measures brought about a dramatic change of circumstances. It underlined that, when change is thrust upon us, many if not all of us are able to adapt our behaviours. Just look a how many people are now working from home.

COVID-19 has also further exposed a fallacy underlying orthodox transport planning, namely that transport supply is led by transport demand. We have come to realise (haven’t we?) that in practice, transport demand is led by transport supply. If it is made easier to go by car, more people are likely to go by car. If the walkability of our built environment is eroded then fewer people are likely, by choice, to walk.

This points to two important observations when it comes to how we can help address decarbonisation, while recognising people will continue to wish to exercise choice. The first is that the relative attractiveness between people’s options in their choice set needs to be influenced (supply-led demand). The second is that it’s not as narrow as transport choices but rather it concerns influencing the relative attractiveness of options for how we access or reach people, goods, services and opportunities in our lives.

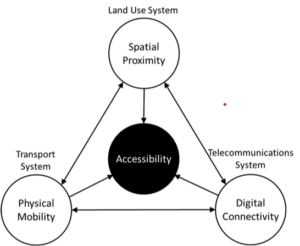

We need to focus on decarbonising access not simply decarbonising transport. A few years ago with my colleague from New Zealand, Cody Davidson, I put forward a simple model called the Triple Access System (TAS). This highlights how the transport system (through physical motorised mobility) can fulfil access. It also highlights how the land-use system (through spatial proximity, along with active travel) can also fulfil access, and how the telecommunications system (through digital connectivity) can, increasingly, fulfil access. These three sub-systems interact with one another forming the TAS.

COVID-19 illuminated two powerful characteristics of this TAS and what it provides: flexibility in how we can gain access and a resilience in terms of being able to maintain access when part of the TAS (the motorised transport system) is restricted.

To tackle decarbonisation calls for Triple Access Planning. It’s fundamentally about rebalancing the supply-side policy and investment decisions concerning motorised mobility, spatial proximity and digital connectivity. This is not taking away choice but changing the relative merits of the choices available. Having spent many years being hypermobile, I have welcomed being able to live local and act global over the last six months. I’ve come to love walking more. I want to see a different modal hierarchy in my neighbourhood (and an end to pavement parking), while being assured of dependable and acceptable bandwidth for digital connectivity. And I will still drive my car on occasions.

I believe Triple Access Planning is the right approach but I’m not naïve enough to think it will be easy. It calls for political appetite to robustly address the supply-side of the equation in a vision-led approach to decarbonisation that provides flexibility of choice while shaping overall demand in favour of lower carbon behaviours.

Glenn Lyons is the Mott MacDonald Professor of Future Mobility at the University of the West of England, Bristol. His paper that introduces the Triple Access System is freely available here

About the Author

This post was written by Glenn Lyons. Mott MacDonald Professor of Future Mobility, UWE Bristol