Whim has recently launched a mobility app in the West Midlands that offers “seamless travel by bringing different modes of transportation into a single app with one monthly fee”. In this case study the Transport Knowledge Hub, with support from Chris Perry (MaaS Global) and Ben Foulser (KPMG), describes what MaaS is, what’s driving the phenomenon, what business models are emerging and what operators and local transport authorities should be doing now to prepare the way for more MaaS applications.

Key Statistics

| Location: | West Midlands |

I keep on hearing the term ‘MaaS’. What does it mean?

The term ‘Mobility as a Service’ (‘MaaS’) originates from the Intelligent Transport Systems sector. Its first use is commonly attributed to Sampo Hietanen, who went on to found MaaS Global.

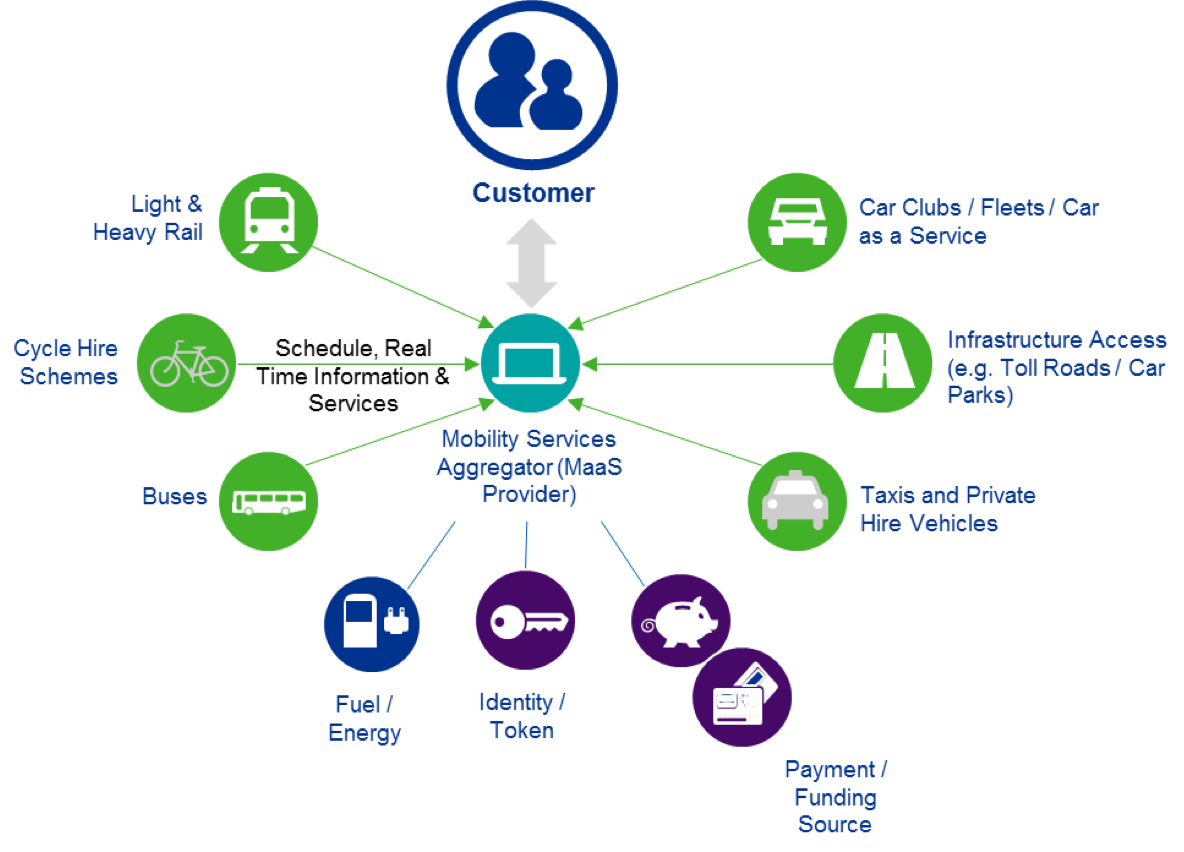

There are several competing definitions for MaaS, but in general, it is taken to mean using digital technology to seamlessly integrate and enhance public and private transport services through better journey information, integrated ticketing and payment systems to meet the complete mobility needs of the customer.

By providing high levels of integration, consumers are presented with all of the possible options for each trip. From commercial and public policy perspectives, travel advice and other incentives can be added to the marketing mix to nudge customer behaviour. For example, at times of severe congestion or poor air quality, the incentive can be offered to customers to change their travel habits.

I’ve heard the expression ‘Transport as a Service’. Is this the same as MaaS?

Transportation as a Service (‘TaaS’) represents a single mode, nominally car/ ride sharing, as opposed to integration of multiple modes to deliver the mobility requirements of a customer. However, TaaS and MaaS are sometimes used interchangeably across the industry; meaning that it is important to understand the context and objectives of any particular project or service to understand which category it fits into.

What is driving this phenomenon?

The availability of data and improved digital connectivity is a significant driver of the development of the MaaS phenomenon. However, equally important, is the changing expectations and behaviours of consumers. Particularly the case amongst the millennial generation is the movement of desire towards experience and service delivery rather than ownership. This can be seen within the music industry – moving away from owning a physical copy of your favourite music to having access to all of the music of your choice through a service provider such as Spotify or Apple Music. In the transport area, new services such as Uber have disrupted both the traditional taxi business and to a degree local bus services. This has been done by utilising a digital platform to provide customers with access to private hire vehicles at the touch of a button with the added reassurance of being able to track your driver and pay through the app rather than worrying about carrying enough cash. The almost ubiquitous penetration of the Smartphone into society enables these services to be available to customers literally at the touch of a button.

Technologies are converging towards common solutions and in so doing are becoming interoperable and easier to integrate between different service providers, and common standards are emerging in respect payment systems. Open data initiatives are incentivising operators to share information to enable aggregation of customer accounts across multiple mobility services providers – although this has not yet been mandated in the transport sector as it has in banking through the Payment Services Directorate (‘PSD2’). The combination of these elements creates an ideal environment for MaaS service providers to draw together timetable, reservation and payments components from across disparate mobility services providers. This is much in the same way as websites such as Compare the Market, Sky Scanner, or Rentalcars.com do for their respective industries, but with the key added benefit of providing the retail mechanism to fulfil access to access each transport mode.

Aren’t industry programmes already focusing on this?

Smart Ticketing on National Rail (STNR) is focused primarily on providing a viable alternative to paper-based, magnetic-stripe ticketing across all rail franchises in the UK. Whilst cross-modal integration is a consideration it is not the objective of this programme. Similarly, other initiatives such as the ‘Big 5’ bus company and Transport for the North (TfN) programme to accept bank card (‘open’) payments is largely focused on a single mode of transport. Although the TfN solution will enable fully multi-modal contactless bank card acceptance for local journeys across the north of England.

One of the most comprehensive payment schemes in the UK is Oyster and Contactless in London, which – predominantly due to the controlled environment for transport in the Capital – can be used across Light Rail, Heavy Rail, Metro (Underground) and River Boat services.

But both the TfL solution and TfN are focussing on providing a payment scheme, without integrating information and journey planning solutions as a core part of their offer. A key ask of the emerging MaaS sector will for the likes of TfL and TfN be to allow MaaS providers access to the relevant back-office systems, in order to allow for third parties to offer services to customers and then be billed by the back office for the travel undertaken by each specific customer.

What business models are emerging in MaaS?

A range of alternative MaaS business models are emerging including:

― Monthly subscription packages

― Pay-as-you-go accounts

― Enhanced first and last mile connectivity

― Information only systems

Transport for the West Midlands and Whim are pioneering a new MaaS scheme in the West Midlands including services provided by Gett taxis, National Express buses, Midland Metro trams, and shortly local train services, city bikes, rental cars and car club vehicles. Customers will have a choice of either pay-per-ride or monthly subscription where customers pre-purchase ‘mobility packages’ that provides the ability for a customer to consume mobility across all providers participating in the scheme up to set limits – a certain amount of travel by taxi, a certain amount of travel by bus, etc. The subscription-based approach is also part of Sweden’s Samtrafiken scheme (originally UbiGo) which includes Västtrafik public transport, Sunfleet car sharing, Hertz car rentals, Taxi Kurir taxis, and Styr & Ställ bike sharing.

The pay-as-you-go model, whereby customers pay for the services they consume, has similarities with Oyster and Contactless account based payment in London including the use of ‘capped’ daily and weekly fares. An alternative variation of the approach is Hannovermobile initiated by Üstra (Hannover’s Public Transport Authority) which for a relatively low monthly fee provides discounted travel by rail, taxi and car sharing.

In the US a number of transport authorities are piloting or even commercially operating schemes where private transport services (predominantly private hire vehicles) are augmenting public transport services to provide ‘first and last mile’ connectivity. For example, the Florida Department of Transportation have engaged Lyft to provide fully-subsidised first and last mile services connecting to bus routes where it is not commercially viable to run a bus the full length of its route, when compared to fully subsidising a Lyft journey. There are various subsidy models for these schemes, but the premise is that the transport authority provides some form of payment integration, be this fully paid for or subsidising reduced fares, thereby integrating public and private transport.

Some players take the view that a MaaS scheme can also be simply premised on information provision. In Vienna mobility services providers wishing to operate in the city are mandated to provide customers with information about other transport services that can be utilised to complete the same journey, especially if the customer is looking to book a private hire vehicle – wherein the customer is shown alternative public transport options. The SMILE ‘Smart Mobility Info & Ticketing System Leading the Way for Effective E-Mobility Services’ platform has been extended to provide customers with a single platform with real-time information, journey routing and ticket purchase and reservations across multiple mobility services partners including Wiener Linien, e-fuel stations (Wien Energie), parking garages (WIPARK Wien), taxi service providers, Citybike Vienna and Carsharing (Drivenow). Other mobility partners include: Car2go (reservation of vehicles), Nextbike (display of locations), Wipark (display of locations) and Zipcar (display of locations). The full platform comprising the aforementioned services is due to be delivered later this year.

What is the trajectory of these type of schemes in the UK?

The first platform that is being officially badged as a ‘MaaS’ scheme has, at the time of writing (November 2017), just commenced a limited trial in Birmingham. However, the company behind the platform has plans to deploy MaaS schemes across more cities the UK, taking advantage of initiatives such as MaaS Scotland; a partnership between Technology Scotland and ScotlandIS which is engaging with organisations spanning the technology, mobility and energy sectors to secure support for development of one or more MaaS platforms.

Other technology solutions providers such as Qixxit and Moovel are also targeting city-specific deployments in the UK market. While initiatives, such as Transport for the North’s Integrated and Smart Ticketing (‘IST’) programme and the Midlands Connect programme, may see the foundations of MaaS schemes being deployed across large regions in the UK through the establishment of Account-Based Ticketing (‘ABT’) schemes. As noted above, MaaS operators will require access to the ABT scheme back office in order to support third party MaaS accounts.

A selection of local and regional transport authorities are also supporting MaaS initiatives. For example, Transport for Greater Manchester’s involvement in the MaaS 4EU project aims to demonstrate MaaS in Greater Manchester, West Yorkshire Combined Authority is supporting Trav.ly and the Scottish Government is supporting Navigogo, a MaaS project for younger people in the Dundee and North East Fife region of Scotland.

There is significant interest in developing and testing MaaS schemes, and a variety of funding sources available both from the UK Government and European Grants – the only commercially operated scheme currently in operation in the UK is the West Midlands pilot. This scheme is operated on a commercial basis by MaaS Global without subsidy, although Transport for West Midlands is providing non-financial support to the scheme in terms of officer support and partner facilitation. The West Midlands pilot will, however, only be successful if enough customers can be generated to make the service commercially sustainable in the longer term.

There are a significant number of hurdles to overcome when designing and deploying MaaS schemes. These include but are not limited to:

― Customer ownership and concerns about mobility providers being disintermediated from their customers

― Risk and liability sharing processes

― Inertia of sunk costs and effort

― Revenue allocation and settlement

― Potential barriers to entry to participation

― Governance and regulations to drive equality and fairness for scheme participants and customers alike

― Customer trust

― Control of funds.

The challenges will likely mean that, whilst pilots and limited-scope MaaS schemes will continue to appear over the short term, it could be several years before we see MaaS schemes of significant scale – both in terms of scheme participation and modal coverage. However, the fact that a commercially funded scheme is now live in the West Midlands will test this assumption. If the pilot is successful and willing partners come together to enable the service, then there are few barriers that could prevent a rapid expansion across the UK. The success or failure of MaaS in the UK will then be down to whether or not the UK market is ready to embrace this new mobility model at levels able to commercially sustain operations.

Furthermore, an effective MaaS scheme relies on there being a sufficient portfolio of mobility services on offer to customers. This indicates that MaaS schemes will initially be most successful in urban areas with modal transport provisions that can realistically reduce (albeit, likely not eliminate) reliance on personal cars, relegating use to demand-responsive private hire (and, ultimately, autonomous) vehicle schemes and periodic use of car club vehicles. As such the time period in which MaaS schemes will be deployed outside of urban areas is significantly longer than within urban areas.

Finally, it should be noted that it may be that more than one MaaS scheme will operate in a region, with schemes differentiating themselves by customer segments and products and/ or mobility provider participation much in the same way that multiple price comparison sites are available today. However, it is likely that, over time, dominant providers will appear which may result in monopoly schemes within cities or regions.

What does this mean for me?

MaaS schemes have the potential to reduce dependency on any one type of transport by reducing and removing the friction of accessing different transport services and allowing individuals to choose the right mode for the journey they are making. In a study of the potential of MaaS in London, UCL found that 50% of people who responded to their research questions indicated that they would be willing to try modes they previously hadn’t used if they were part of a MaaS scheme and 23% of car owning respondents agreed that MaaS would help them depend less on their cars, with 20% noting a willingness to sell their cars for unlimited access to car sharing for the next couple of years[1].

In Helsinki, where the first iteration of the Whim platform was launched in 2016, use of public transport increased from 48% to 74% of all journeys made by scheme members, with car journeys halving from 40% to 20%. These results are encouraging and will, no doubt, prompt interest in exploring opportunities associated with MaaS.

There are, however, a number of different areas that should be considered before jumping into deploying a MaaS scheme. Like the challenges above, these are too numerous and complex to be covered in this case study however key considerations include:

― Developing a clear understanding of how a MaaS scheme might impact (positively and negatively) the delivery of local transport policy objectives, e.g. accessibility and delivery of concessionary travel.

― Developing scenarios that may play out through a MaaS scheme and identifying if any of these scenarios could lead to a potential market failure.

― Recognising that changing modal demand and travel patterns resulting from customer participation in MaaS schemes may change land-use needs and, accordingly, incorporating agility within infrastructure plans.

― Determining what new alliances may be required and how this might impact stakeholder dynamics and relationships in the existing infrastructure.

― Assessing what existing infrastructure and investments can be leveraged to support the deployment and operation of a MaaS scheme, including what changes (e.g. Open Data initiatives) or new infrastructure may be needed’.

― Determining on what commercial basis a supplier would be prepared to participate in a MaaS scheme including: scheme cost allocation, revenue allocation and settlement, revenue risks and liabilities, and clearly articulating this to the MaaS scheme operator(s).

― Assessing the value of current relationships with customers (from both a commercialisation and control perspective) and the extent to which this relationship may be lost by participating in a MaaS scheme.

― Determining the extent to which your organisation may look to be the MaaS scheme provider and/ or systems operator in order to enable you to deliver your strategic objectives.

MaaS as a concept can provide highly attractive propositions for local authorities, operators and customers alike, but require careful planning and consideration in order to maximise their value and reduce the risk of adversely impacting policy objectives.

[1]Kamargianni, M., M. Matyas, and W. Li 2017. Londoners’ attitudes towards car-ownership and Mobility-as-a-Service: Impact assessment and opportunities that lie ahead. MaaSLab – UCL Energy Institute Report, Prepared for Transport for London

Summary

Whim has recently launched a mobility app in the West Midlands that offers “seamless travel by bringing different modes of transportation into a single app with one monthly fee”. In this case study the Transport Knowledge Hub, with support from Chris Perry (MaaS Global) and Ben Foulser (KPMG), describes what MaaS is, what’s driving the phenomenon, what business models are emerging and what operators and local transport authorities should be doing now to prepare the way for more MaaS applications.

Submit your Case Study

If you have a case study that you would like to be included on the Hub, please submit it using this form.